Edith Sitwell | Part 2

In her second blog, Katie looks at the ways in which Edith Sitwell supported talented young writers, as well as exploring Sitwell’s own achievements as a writer.

In her Face to Face interview with John Freeman in 1959, Edith Sitwell listed her hobbies as ‘reading, listening to music and silence.’ However, when it came to publicising and assisting her friends, she was far from silent. D.N. Thomas, in Dylan Thomas: A Farm, Two Mansions and a Bungalow, notes writer I.G. Bartholomew’s stories of how Edith Sitwell enthusiastically championed Dylan ‘both as a man and a poet.’

Early in their correspondence, Edith had recommended that Dylan find a form of employment and, after the publication of Twenty-five Poems, took matters into her own hands to get him work. Andrew Lycett, in Dylan Thomas: A New Life, documents that she approached Richard Jennings of the Daily Mirror to get him a job. She subsequently turned to writer and historian Sir Kenneth Clark for assistance. Although neither attempt was successful, her influence on Dylan directly produced better results. According to Lycett it was at her suggestion that Dylan hired David Higham as his literary agent. This was a fortuitous pairing as Higham became ‘skilled in bailing Dylan out of difficult situations.’ In February 1938, James Laughlin of the American publishing company New Directions contacted Dylan in the hope of publishing his work in America. As Lycett notes, Dylan’s work was originally brought to Laughlin’s attention by Edith Sitwell.

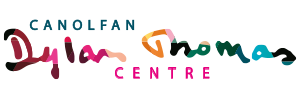

Caitlin, in her autobiography Caitlin: Life with Dylan Thomas talks of how fond Sitwell was of Dylan, saying how she would invite them both to her parties at the Sesame Club and introduce Dylan to influential people. Caitlin describes her as ‘quite extraordinary, dressed in turbans and bangles… a grand eccentric.’ Indeed, Edith’s unusual sense of dress was often commented upon. When John Freeman asked her about it in an interview, she replied that if she wore coats and skirts people would ‘doubt the existence of the Almighty’.

Although Edith’s poetic output had been limited during the 1930s, in the 1940s she began writing a significant amount of poetry. ‘Still Falls the Rain’ which was published in the Times Literary Supplement in 1941 was a response to the Blitz in London and was to become one of her better-known poems. In 1954 Benjamin Britten set the words to music in his Canticle III: Still Falls the Rain, for tenor, French horn and piano. This was not the first time Edith’s words had had a musical treatment. With Façade, in 1922, her poems were recited over a musical accompaniment by William Walton.

By 1946 Dylan was restless to travel to America with Caitlin. According to Paul Ferris in Dylan Thomas: The Biography, Edith did not approve of the idea and tried to dissuade him, worried, Ferris says, about the ‘prospect of a penniless Thomas in America’. However, she did recognise a deterioration in him and, as Constantine Fitzgibbon notes in The Life of Dylan Thomas she was ‘anxious that the spiral should somehow be broken.’ Again, she intervened by, as Lycett documents, prevailing upon the Society of Authors- of whom she was a committee member- to award Dylan a £150 travelling scholarship. He used this to take himself and his family to Italy, where he worked on ‘In Country Sleep’.

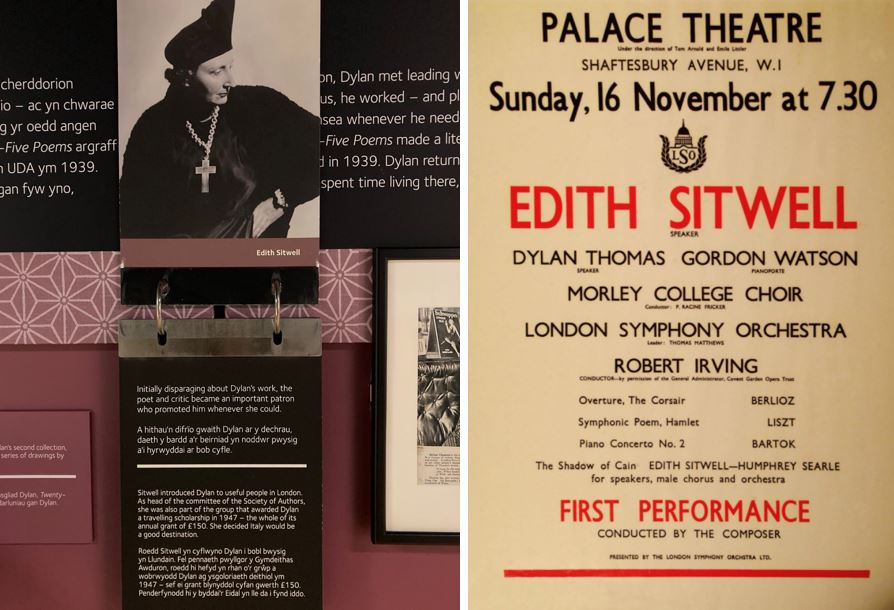

Dylan frequently read Edith’s work for B.B.C. poetry programmes. In the February 1954 edition of Atlantic she said hearing him read her work ‘was a great pride’ to her. In the same article she writes that he had ‘a speaking voice of the utmost magnificence, range, and beauty’. It is little wonder that she therefore requested him to share the reading of her poem The Mark of Cain in November 1952. Another of her works to be put to music, this time by Humphrey Searle, it was a protest poem about the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Lycett documents that Dylan performed the poem again, this time on his own as Sitwell was in America, on the 13th January 1953 at the Royal Albert Hall, broadcasted by the B.B.C.

After Dylan’s death, Edith wrote in the Atlantic ‘His loss to poetry and to his true friends is not to be borne’ and she continued to defend and promote both the man and the poet. She composed a ‘personal tribute’ which was read at a gala held at the Globe Theatre for the Dylan Thomas Memorial Fund in January 1954. In the November 1955 edition of Poetry, her Elegy to Dylan Thomas was printed. In her Face to Face interview of 1959 she described Dylan as always behaving ‘impeccably’ around her.

Dame Edith Sitwell died on the 9th December 1964. She was 77. You can listen to her reading ‘Still Falls the Rain’ at https://poetryarchive.org/poet/edith-sitwell/

Katie Bowman, Dylan Thomas Centre

This post is also available in: Welsh