Dylan’s Writing Spaces: Dylan in Donegal

In the second of her blogs on Dylan’s writing places, the Dylan Thomas Centre’s Linda Evans looks at his time in Donegal.

In mid-September 1935, Dylan Thomas wrote from Swansea to writer Desmond Hawkins: ‘I’ve been on the blindest blind in the world and didn’t know what day it was or what week or anything’. He had recently returned from what we might now think of as a small-scale ‘writers’ retreat’ in an exceptionally remote area of Co Donegal, Ireland.

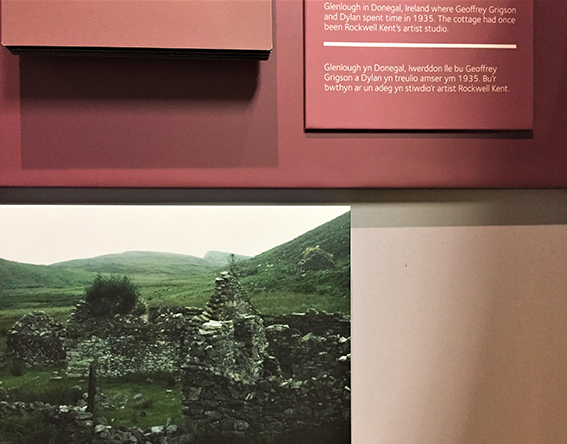

In early summer he travelled from London to the cottage at Glen Lough, with Geoffrey Grigson, a poet, critic, and editor of the influential poetry magazine ‘New Verse’. He suggested the twenty-year-old prodigy accompany him on holiday, giving Dylan the opportunity to recuperate and regroup away from the temptations of his habitually louche and heavy-drinking bohemian lifestyle. The pair rented a converted cow byre from farmers Dan and Rose Ward that the famous American artist, writer, and traveller Rockwell Kent had converted into a basic dwelling back in 1926, where he produced some very fine paintings of the locality.

The original focus for the young men was on ‘clean living’ – i.e. eating nutritious food, taking fresh air and exercise on long walks by mountains, lakes and the coast, with its abundant wildlife and giant rocks fronting the Atlantic Ocean. Geoffrey even taught Dylan how to catch trout. In the evenings they lit a peat fire and talked by candlelight. Overall, it was an enjoyable and deeply sensory experience. However, after a fortnight Geoffrey returned to London, leaving Dylan, at his request, alone. Henceforward he all but shut himself off from the outside world. Without distractions, he inhabited a deeply-focused state of mind brimming with creativity. But gradually he became disenchanted by the silence and loneliness, despite enjoying regular meals and supplies of poteen (or poitin), an illicit locally-produced whisky, provided by his landlords. His cigarette supply dwindled, he longed for social interaction and a companionable pint of porter was only obtainable by ten-mile often damp, squally and midge-ridden treks to O’Donnells pub in Meenaneary.

He wrote long letters to Swansea friends: ‘I can’t indefinitely regard my own face in the mirror as the only face in the world’, and in his isolation he became sentimental for the normality of his known world: ‘I feel the need for that world, the necessity of its going on’. Although Dylan had hoped to stay until September, he reached a tipping point. Despite attempting to keep to a routine, taking walks after dark, then ‘padlocking out the wild Irish night’, his mental health suffered: he had night terrors, saw strange figures and felt strange crawling skin sensations. Undoubtedly his vulnerability was exacerbated by local supernatural superstition, feeding off the wildness and ruthlessness of nature and the elements.

At the end of August Dylan upped and left Glen Lough suddenly, without paying the rent, snubbing the Wards’ kindness, and much to the anger of Geoffrey, who had left him money. The young bachelor made his way back to Swansea (and the doting attentions of his mother), returning with several exceptional new poems, including ‘I in my intricate image’ and ‘Altarwise by owlight’, which later appeared in his second collection Twenty-five Poems, published in 1936 to critical acclaim.

Linda Evans, Dylan Thomas Centre

This post is also available in: Welsh