A Poem in the Chamber Pot | Part 2

In the second and final part of her blogs exploring the life and work of Tambimuttu, Charlotte discloses Tambi’s unique filing system.

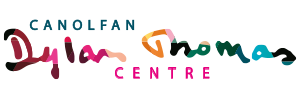

If we are to agree with cultural historian Barry Miles’ summation that Meary James Tambimuttu was ‘a literary hustler of exceptional ability’[1] then we might wonder what trouble was stirred when he met his Welsh equivalent in Dylan – a fellow hustler if ever there was one. Away from the pubs, this creative pair certainly knew each other well enough to have corresponded, and several of Dylan’s letters to Tambimuttu can be found in The Collected Letters[2]. These letters betray the chaotic ‘professionality’ of both parties: Dylan rarely providing the promised work and Tambimuttu rarely providing the promised payment. Other letters that Dylan wrote about Tambimuttu, are frequently scathing of the man that held so much sway amongst the ‘literati’ of London[3].

There was a particularly unfortunate incident involving Tambimuttu’s errant filing system. If the Poetry London editor read a poem or manuscript in bed (a favoured reading spot) that did not meet his needs, he simply reached underneath the bed and shoved it into his chamber pot. This receptacle would become positively stuffed with rejects from his late-night readings. On one occasion, Dylan’s work was obviously not up-to-scratch, and ended up in this ceramic dumping ground. When Dylan repeatedly asked for the return of his poem – of which Tambimuttu had the only copy – he was reportedly incensed to discover its whereabouts![4]

This unconventional approach fed into persistent rumours that liked to downplay Tambimuttu’s literary commitment. It was alleged that he didn’t even read the work that was sent to him – casting his publication of some of the greatest creatives of his time in an almost providential light. Certainly, many of Tambimuttu’s friends and colleagues profess to a kind of wonder at the ways in which he selected the poetry and artwork for his projects.[5] However, Barry Miles speculates that rumours of his unconventionality were likely cultivated by Tambimuttu himself, in a playfulness that was also noted by his contemporaries.

Tambi ate little and drank a lot, but his contribution to English literature was enormous: he edited fourteen issues of Poetry London, and more than sixty books of poetry and prose…featuring everyone from Dylan Thomas, Louis MacNeice and Stephen Spender to Lawrence Durrell, W.S. Graham and Katherine Raine.[6]

This level of success and commitment cannot be attributed to chance and Tambimuttu should be viewed today as being at the centre of the literary scene. It seems fitting to end this short exploration of his life with an extract in his own words. Recalling a documentary that was made shortly after the war, he notes that he was pleased to see that some of the scripts had been commissioned from ‘the impoverished Dylan Thomas.’ He goes on to note the ways in which the situation would later reverse itself:

When I was impoverished myself, in New York, I sold a letter from Dylan to the House of Books, New York, which read: “Dear Tambi, Please let me have the guinea you owe me for my last poem. Yours, Dylan.”[7]

We can only hope that the poem in question had earned its place out of the pot.

Charlotte Rogers, Dylan Thomas Centre

[1] Miles, Barry, London Calling, Atlantic Books: London, 2010, p. 11

[2] Ferris, Paul, Dylan Thomas: The Collected Letters, J. M. Dent: London, 2000

[3] Several examples of Dylan’s thoughts on Tambimuttu can be found within the Collected Letters however it is worth mentioning that Dylan rarely spares anyone from criticism, especially those that hold the power of publishing him.

[4] Miles, London Calling, p.12

[5] Williams, Jane, Ed., Tambimuttu: Bridge Between Two Worlds, Peter Owen: London, 1989

[6] Miles, London Calling, p. 13

[7] Williams, Tambimuttu, p.228

This post is also available in: Welsh